One question I get asked repeatedly, in every talk about Healthcare IoT and sensors, is about trust and data quality – Can I trust the data I see? The use of IoT in the health sector has seen the development of new applications in this sector. Wearables are being used to monitor patients, drug delivery systems, personalized treatments based on activity, and tele-based healthcare solutions. Data can be noisy and erroneous as it comes mostly from heterogeneous devices that suffer from battery and accuracy issues. The privacy of the users is a significant concern. I have written a few articles on IoMT, its adoption, opportunities, and security-related subject previously, so I wouldn’t repeat myself, but you can find them in my other articles here. Let’s start with the questions I usually come across: –

Will a clinician trust data from IoT sensors or devices?

What are the factors that influence human trust in IoT data?

Can trust in medical IoT be optimized to improve decision-making processes?

The adoption of medical IoT in healthcare depends on data being collected and secure transmission for processing. Because of the nature of the healthcare vertical, clinicians are always concerned about the trustworthiness of data, which in fairness, has failed to prove itself on some occasions in the past. By “data trustworthiness”, I mean that the data used as the basis for making decisions is the right one from the right patient. Hence, deciding the data trustworthiness is an important consideration not only for the health experts but also for the technology experts who believe in future IoT-health innovation. The topic of data quality is the primary concern and possibly ‘make and break’ for any IoT-based medical solution.

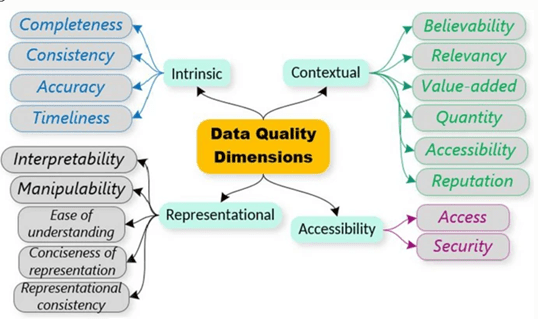

Let’s dive a little deeper into the problem statement – it is essential to determine the quality of data shared between IoT domains to facilitate the best decisions or actions. The importance is compounded in IoT environments when data is derived from low-cost sensors, which may be unreliable. It has been widely adopted that each application requires a unique description of data quality (DDQ). For data to be shared, these unique descriptions must be standardized and advertised. Data quality can be described and evaluated using DQDs. DQDs provide an acceptable, standardized, flexible, and measurable set of quality metrics to measure data quality. Before I go further into DQDs, I will explain data quality using four properties: intrinsic, contextual, representational, and accessibility. For each of these properties, appropriate DQDs are given.

Clinical decisions can be negatively impacted by poor data quality. Several factors which can degrade the quality of data in an IoT context include deployment scale, resource constraints, fail-dirty, security vulnerability, and privacy preservation processing. These manifest differently at different stages of the AI models which are applied for clinical decision capacity. For example, fail-dirty, sensor fault, and deployment scale are more predominant during data generation, as privacy preservation processing manifests mostly during data use and storage but altogether, they deteriorate the overall accuracy of clinical decisions and eventually trust!

Generally, the quality of data is highly dependent on the intended use and this is a multidimensional concept that is difficult to assess as each use case defines its quality properties. There are four categories of data quality properties that I believe any assessment system should be able to implement collectively rather than in isolation. These include:-

Intrinsic: This category examines quality properties in the data itself. For example, data quality may be looked at in terms of how a sensed point deviates from an actual point (anomaly detection) or how a particular data point differs from the rest of the data.

Contextual: This looks at quality properties that must be considered within the context of the task at hand. For example, it must be relevant, timely, and appropriate in terms of quantity. This property of data quality has previously been neglected.

Representational: This looks at computer systems that store the information. They must ensure that the data is easy to manipulate and understand.

Accessibility: This looks at data quality challenges that are as a result of the way users access the data systems. For example, it could be from the insecure, unregistered network where new packets can be introduced into the data thus affecting its quality.

Each of these data quality properties defines quality metrics that can be used to assess data quality. These are collectively known as data quality dimensions. Examples of these include but not to accuracy, accessibility, timeliness, believably, and relevancy.

Factors that affect data quality in healthcare IoT exist throughout. For example, during data generation, data quality may be affected by sensor fault, or environmental factors; during data transfer and pre-processing, network outages may impact data quality, and factors such as privacy preservation processing affect data quality during storage and use. There is a need to evaluate data quality at each stage, store such scores or add them as metadata and combine them into a single metric that can be advertised to data consumers in real-time.

Understanding data quality manifestations at each stage helps us not only to solve data quality challenges but could also inform the usability of tools used at such stages. For example, data quality score at the data generation stage could be used to automatically recalibrate sensors (a decrease in quality score over time could be correlated with calibration errors), or data quality scores during modeling can be used to tune automatically tune machine learning models. I will finish this episode on the note that introducing IoT systems, involving advice from AI to support the clinical decision, requires more than just functionality. There is a need to increase the trust of users in the reliability and accuracy of data and as AI moves from the currently acceptable narrow intelligence directed by clinician-determined action plans to a future in which advice is generated by the IoT system. Our technologically adept participants are not yet ready for this step; research is needed to ensure that technological capability does not outstrip the trust and data quality concerns of the individuals using it.